Putting the “Structure” into Structured Literacy: Part 2

I compared one popular reading program which uses a small group for all philosophy and my foundational skills block. Students in the popular reading program would receive 60 minutes of foundational skills instruction per week and 240 minutes of independent work time. In my foundational skills, block students are receiving 45-60 minutes of instruction per day and only 10-15 minutes of time is expected to be independent for students who are at or above grade level expectations. During the independent practice time students are either practicing reading or writing connected to the skill we are learning. This will drastically increase the amount of instructional time students receive.

Planning Literacy Instruction: When You Know Better and Want to Do Better

I’m writing this blog post to share some high-leverage, high-impact shifts teachers should be making regardless of their curricular materials. These shifts can be implemented tomorrow, and they are free. Additionally, these are shifts that work well in grades 3+. As an upper elementary, middle or high school teacher, it can be tricky entering this space. There seems to be an abundance of information and resources for k-2 teachers. The need for the instructional shifts highlighted by the science of reading is just as acute in upper elementary and middle school classrooms.

Teachers Leading Change

Are you a teacher who is passionate about the science of reading, structured literacy, and ensuring all kids learn how to read? Are you interested in becoming a change-maker? Are you trying to lead change in your classroom, school, or district but not sure where to begin? Leading change can be an overwhelming task. It’s hard to know where to begin. It makes sense to start in our classrooms, but can our reach go beyond our classroom doors? Here are some ideas of how to create change in three different spaces.

Putting the “Structure” into Structured Literacy Part 1

I then began to just use small groups sparingly after reading the book Focus by Mike Schmoker. Letting go of the small reading groups was one of the hardest instructional shifts I made. It was also the shift that I believe led to greater outcomes in student achievement. I was able to emphasize our whole class and individual needs in foundational skill areas using a systematic phonics program and aligned diagnostic assessments.

The Shift From Skills to Content

Instead of teaching comprehension as a set of skills, I now teach content. The Knowledge Matters Campaign is a great place to start to look for a content rich curriculum. Our ELA block no longer consists of modeling with trade books followed by independent practice. I outline each ELA lesson using the LETRS comprehension checklist. We begin by establishing our purpose for reading. Why are we reading this? What should we take away from the text? We quickly identify text structure and move onto vocabulary. I teach 3-5 tier 2 and 3 words per lesson. For each tier 2 word, I follow the LETRS 5 step sequence…

5 High-Impact Strategies for Reading Intervention

Below I will outline 5 evidence-based practices that I consistently utilize and layer into the curricular lessons I have been tasked with implementing this school year. One of the most challenging tasks posed to teachers is how to translate research and knowledge into classroom instruction. Specifically, what does evidence-based instruction look like, and how does it fit with what I am required to teach? Oftentimes after attending a professional development session I like to immediately try out a practice in my intervention space. If I find it to be effective with the students in front of me, I will try and find more ways to incorporate that practice. Here are 5 of the most effective strategies I’ve had a chance to embed in my curriculum and implement with intervention students this school year.

Who Says You Can’t Add Meaning to Foundational Literacy?

I’ve heard many questions about teaching early elementary students how to become skilled readers:

“How can decodable texts address reading comprehension?”

“How can you make time to incorporate both meaning and decoding into structured literacy lessons?”

“How can you incorporate meaning into word or sentence dictation?”

“How can the science of reading prepare students for the rigor of the upper elementary grades?”

In this blog, I’m going to provide some tangible examples of how I embed language comprehension into every structured literacy lesson.

Learning Styles for Lunch: What I Wish I Had Said

What we say and how we say it matter, even in smallest, more forgettable moments. A positive interaction in the faculty lounge might mean that the first grade teacher downloads a podcast you recommended for her commute. A perceived slight might mean that the second grade teacher tunes out the next time you start talking about knowledge-building. We aren’t going to change a person’s mind in a single interaction, but a single interaction can certainly change the course of a relationship.

Washing Our Hands of the Reading Wars

We need to start talking and thinking about systematic phonics and the science of reading not as a cure-all, but as a standard of care. It is not just the initiative of the decade; it’s a non-negotiable that rests at the foundation of all literacy instruction. It’s just how we teach kids to read. It’s how we care for our students, especially our most vulnerable and marginalized.

Professors are People too

Here’s my bottom-line:

We cannot change and improve reading instruction without changing teachers’ minds.

We cannot change and improve educator prep without changing professors’ minds.

The most effective advocacy will center both of those ideas.

Reading Reform Across America: The most interesting thing I read this summer…

Inevitably, this analogue report would be harder to write and compile–where do you even begin? But when I think about changing the way reading is taught, when I think about persuading teachers and school leaders that this whole structured literacy thing isn’t just another initiative that will die on the vine after a few years, I’m way more optimistic about bottom-up, opt-in initiatives that incentivize educators and recognize that educational change cannot be mandated overnight.

Crowdsourcing Science of Reading Wisdom

In this padlet, we’ve compiled a list of questions that we expect to encounter as we start these conversations. We believe that these are important questions that can be difficult to answer on the spot. For that reason, we invite YOU to share ideas, practiced responses, and helpful resources that can support teachers, interventionists, administrators, and anyone else who needs to speak to the importance of evidence-based practices on both sides of the reading rope.

Socratic Seminars for Beginners: Learning to “Let Go”

On a final note, I must reiterate the importance of letting go once you get started. Although there will be a good amount of preparation you will do “behind the scenes” prior to a Socratic Seminar, students must “take the reins” during the actual discussion. It will not always be perfect and there will be mishaps along the way, but allowing students to take ownership of their ideas and work through minor moments of struggle will cultivate growth. Be prepared to “let go,” pull up a chair outside of the Socratic Seminar circle, and watch the magic happen. The true reward and joy will be found in watching your students lead each other to new ideas, questions, and even shared understandings. And the best part? They will have done it all on their own.

Student-Structured Literacy

Including Student-Structured Literacy elements into my approach to teaching foundational literacy was a game changer for me. Not only was I able to teach phonemic awareness and phonics in keeping with best practices from the science of reading research, I saw students engage in a more joyful and collaborative way as they took ownership of their literacy learning through a more culturally responsive model. If you are an early literacy practitioner, consider adopting this framework as you plan for effective and engaging reading instruction next school year. Start small by trying just one of these options and you might be amazed to see where the kids lead you with their creativity and leadership in literacy.

Standard Celeration Charts

It’s worthwhile to learn how to use this tool to monitor student progress and to inform instruction. There are programs that can generate digital charts and even some that can program in the data for you. There are many ways this chart can be used, and it is highly adaptable. You can measure almost anything. I’ve seen some precision teachers who can build up a wide variety of cognitive and behavioral skills as well as academic skills. There are limits to this tool, as there are with every tool, but it is a powerful option for building up our students’ skills.

Bridging Research to Practice: Mount St. Joseph University’s Reading Science Programs

Whether it’s called The gap between reading research and classroom practice, The missing foundation in teacher education, or The two cultures of science and education, the research consensus is clear: there is a major chasm that exists between reading research and reading instruction. In fact, the disconnect between reading science and the teaching of reading is so significant and substantial that those “labels” are all chapter titles in books written by prominent researchers in the field of reading science: David Kilpatrick, Louisa Moats, and Mark Seidenberg, respectively.

SIPPS 101

The next day we had to sit in multi-grade level bands, with first and second grade seated together. I quickly learned that SIPPS is best used as differentiated instruction across multiple grade levels. If a teacher were to teach SIPPS in just their classroom, they would be limited to roughly two small groups. There simply wouldn’t be enough time to differentiate beyond that. However, by combining both first and second grade, suddenly we have 6 teachers for 12 small groups. That flexibility allowed us to fine-tune our differentiation down to whether a student was struggling with sight words or sounds within the same series of lessons.

Fellowship Application Reflections

These videos have been a delight to watch. Among many other things, this morning I’ve watched:

3rd graders participating in a Socratic Seminar about who gets to decide the meaning of a work of art.

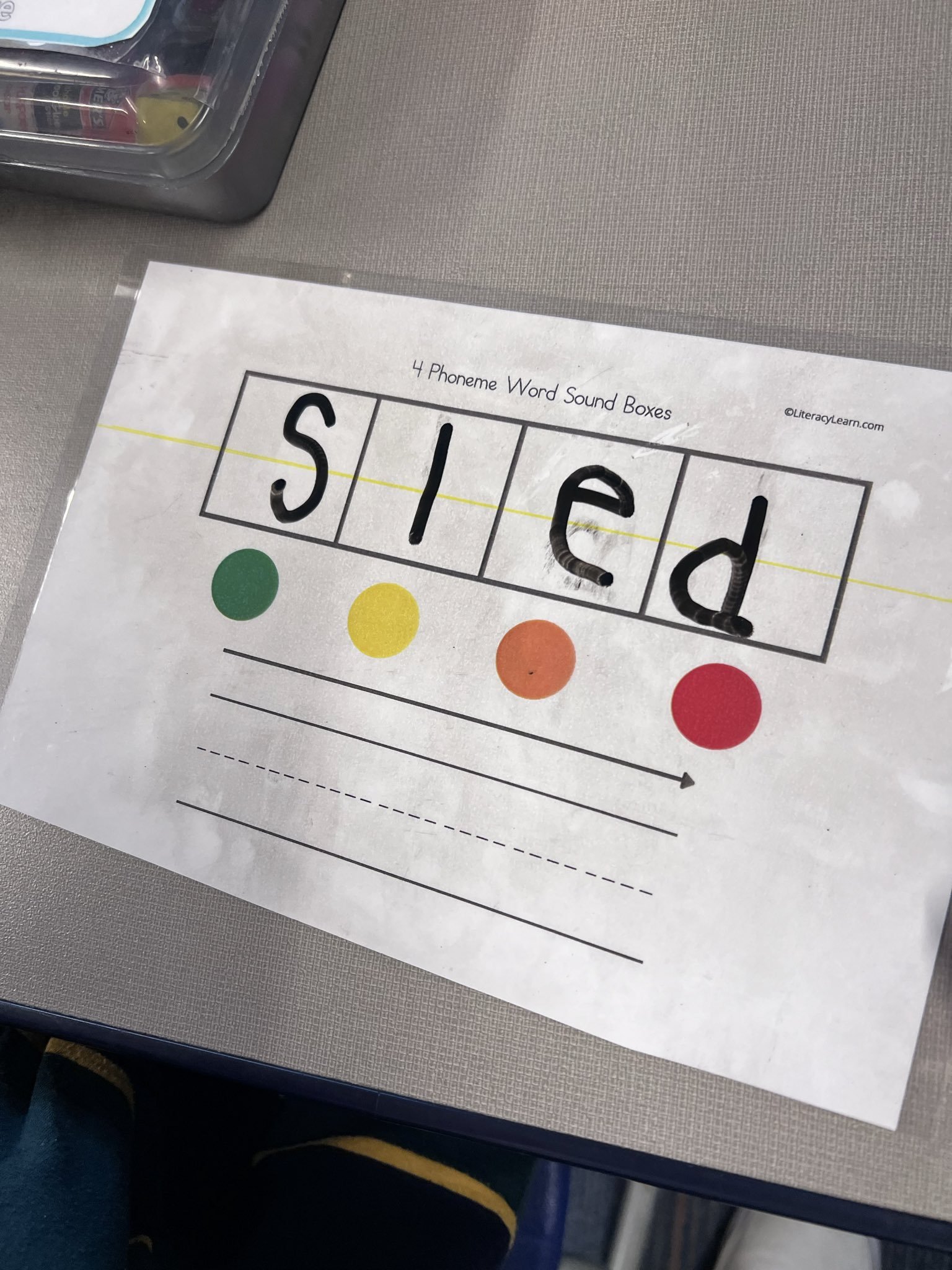

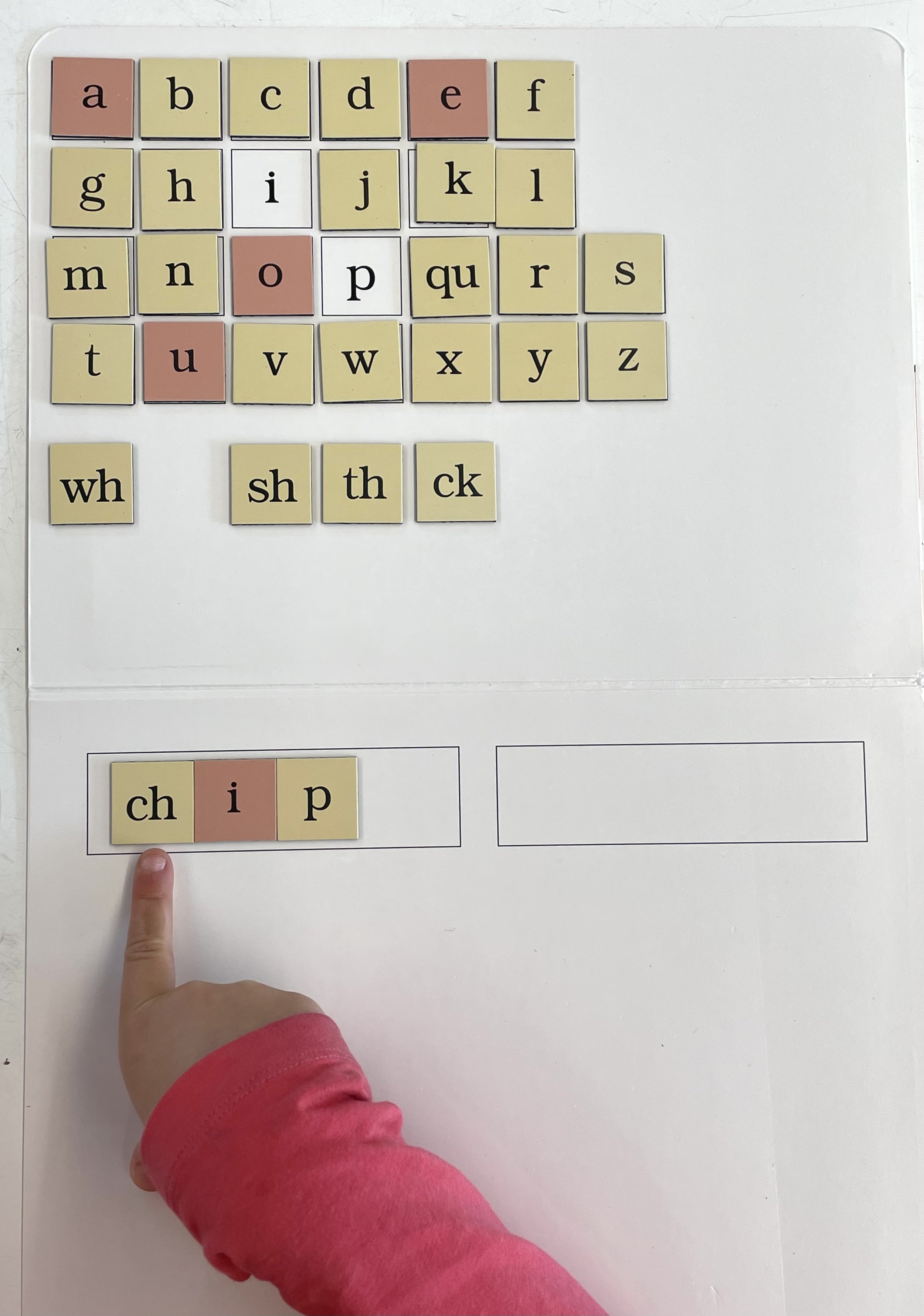

Kindergarteners decoding and encoding multisyllabic words.

A 7th grader teacher leading sixty (yes, sixty) 7th graders through a fluency review to prepare for state testing.

Roadmap to Reading: Implementing Evidence-Based and Data-Driven Literacy Instruction at Marin Horizon School

“I think we’re getting smarter!” declares an enthusiastic kindergartner after impressing himself with his participation during phonemic awareness “word games.” Students notice that breaking words apart into sounds - such as cat into /c/ /a/ /t/ - feels easier than it had in the beginning of the year. From a different spot in the same classroom, other students are excitedly noticing all of the parts of the day’s schedule that have newly-introduced digraphs: “math!” “Spanish!” “lunch!” There are few things more exciting than being five or six and learning that the written stuff all around you is a code that you are learning to break.

How My 1st Graders Learned the Word “Observe”

Fast forward one month, my five students at my small group table opened their new Geodes text, ‘Bee Waggle.’ In this set of four Geodes texts, students learn about Vervet monkeys who communicate different alarm calls to warn about different predators, about ants who communicate using scent, elephants who communicate in many different ways, and bees who have dances to communicate the location of nectar. My students read the page.